The Materialist and the End of the World

March 23rd, 1967 @ 12:00 PM

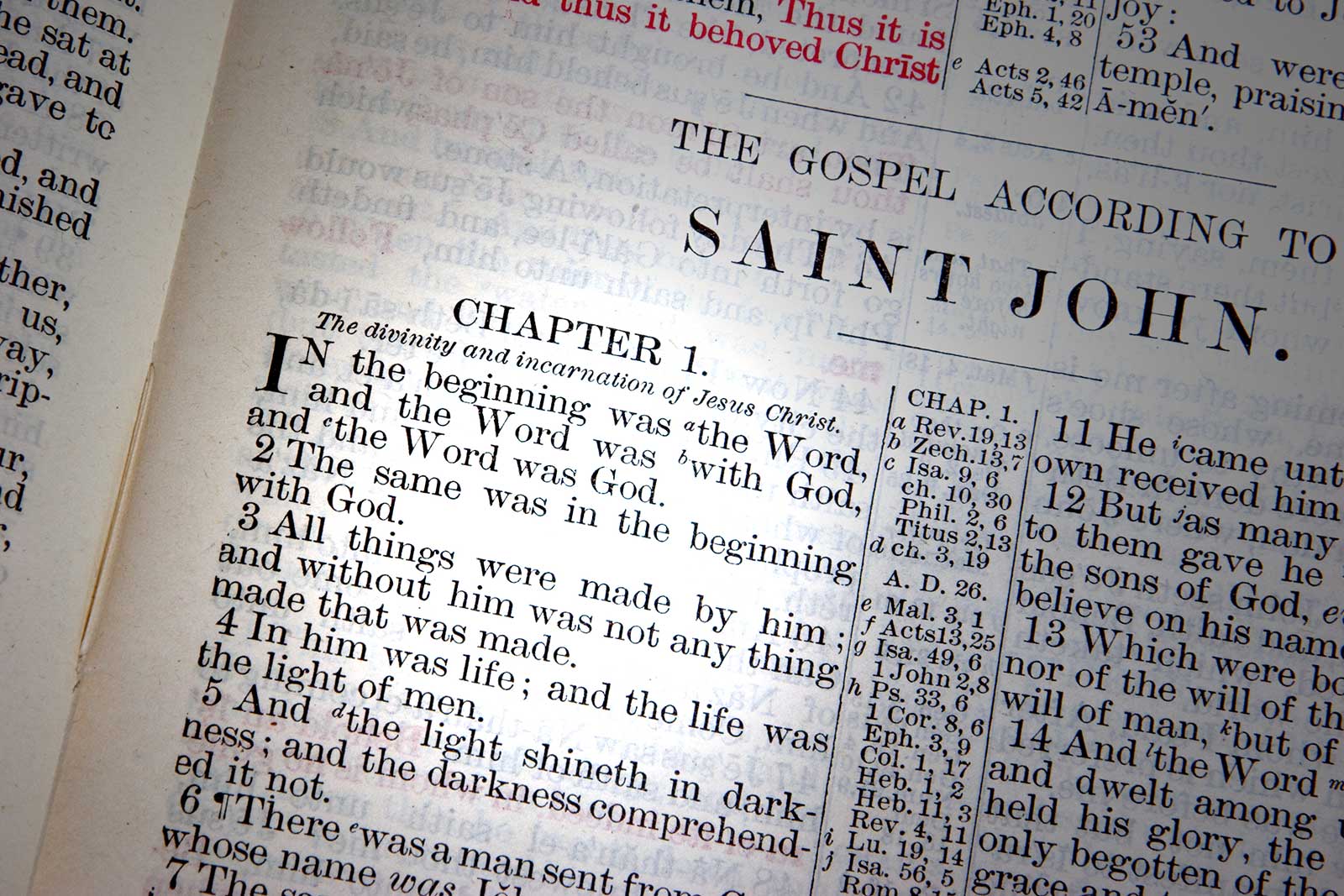

Hebrews 11:3

Related Topics

Conversion, Creation, Hopelessness, Materialism, Science, Secular, In Defense of the Faith (Pre-Easter '67), 1967, Hebrews

Play Audio

IN DEFENSE OF THE FAITH:

THE MATERIALIST AND THE END OF THE WORLD

Dr. W. A. Criswell

Hebrews 11:3

3-23-67 12:00 p.m.

As most of us would know, this is the forty-eighth year that our dear church has conducted services in a downtown theater. Forty-eight years ago there was no Palace Theater, and Dr. Truett began them in the Jefferson Theater down the street. Then two years later, this building was erected, and from that day until this these noonday pre-Easter hours have been convened in this spacious auditorium, it has been given to us through the years. The only cost we pay for is the cost of the union labor in setting it up and taking care of the hour. And we could never thank the Interstate System, Ted Steinberg, Mr. Cherry, all those wonderful people, for being so good to us.

Now the theme of the messages this week has been “In Defense of the Faith.” Monday, it was The Atheist and the Reality of God; Tuesday; The Liberal and the Deity of Christ; yesterday; The Communist and the Living Church. Tomorrow, Friday; it will be The Sinner and the Sacrifice on the Cross. Today it is The Materialist and the End of the World. In the eleventh chapter of the Book of Hebrews and the third verse it is written, “By faith we understand that the worlds were framed by the word of God” [Hebrews 11:3]. Genesis 1:1, “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.” And as we proceed in this brief message we shall return to those inspired revelations from the Lord.

America is a material and secular nation, increasingly so. Our gods are those of technology, and scientific advancement, and the things and the gadgets of life. Our standards of success are measured by worldly values; we love status symbols and the trappings of the affluent society. One of these typical stories concerns a Texas tycoon, with his vast spread of oil wells, who requested that he be buried in his gold-plated Cadillac. So when he was deceased, in keeping with his last will and testament, they dug a big yawning hole, and a crane picked up his gold-plated Cadillac. And in the awe and the hush as they lowered him down in the hole, a fellow was overheard to say, “Man, ain’t that living?”

And I do not know how many places I have heard the story told about the Dallas dowager who, translated to glory, appeared at the pearly gates. And when the keeper asked for her credentials, she laid before him a charger plate from Neiman Marcus. She placed by the side of it a cancelled ticket to the Dallas Civic Opera. She added to it a membership card in the Dallas Country Club. And the gate keeper said, “Well, madam, come on in, but I’m telling you now, you ain’t going to like it here.”

It is difficult for us to learn from the lessons of the past: the emptiness, the futility, the transitoriness, the ephemerality of things material. It was Nebuchadnezzar who, standing atop of his gorgeous palace and looking over the vast ancient city of Babylon, said, “Is not this the great Babylon, that I have built by my own power, and for the glory of my own majesty?” [Daniel 4:30]. Babylon is a mound of dust and a pile of mud and has been for millenniums. One of the most famous and beautiful in meaning of all of the sonnets in the English language is this one entitled Ozymandias by the English poet Shelley. He wrote:

I met a traveler from an antique land,

Who said, “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read,

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my works ye mighty, and despair!’

Nothing else remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

[“Ozymandias,” by Percy Bysshe Shelley]

The materialist, the secularist leaves God out of the world. All values to him are material.

In a Pullman car, a man was working out a crossword puzzle. And bewildered, he finally said to his companions around, “What a strange word, ‘man’s best friend,’ and the middle letter is ‘o’.” And amused they said, “Why, that’s ‘dog’.”

“No,” he said, “for it seems that the last letter is not ‘g’ but ‘d’.” And it never occurred to him, nor to any of his companions, that the word might mean God.

To the materialist, there is no other reality in the world but physical substance. And all phenomena, including that of mind, intelligence, and personality is no other thing but the result of physical agencies. When he turns to the beginning [Genesis 1:1], he says, “Out of nothing is something.” And this something of itself shaped itself, designed itself, rearranged itself, and we have the world and the phenomenon of life itself. Then when he turns to the end of the world he says, “The end of the world will be as the beginning.” In the beginning it was a fortuitous concourse of atoms that gathered without meaning. And the end will be the disbursement, the scattering of those same atoms without purpose. And the universe, and all that is in it, shall die when the force of the sun burns out. This is the materialistic worldview of the universe and the meaning of life.

Now let us look at it for just a moment: first, the beginning. A man comes up to me and he says, “That’s a fine watch that you have there on your wrist.” I say, “Indeed it is a magnificent watch. And you know what? The parts just came out of nowhere. I put them in a box and I shook it for two hours. And when I opened the lid and looked in there was that watch all arranged, running, and keeping perfect time.”

And the fellow says, “You don’t expect me to believe that do you?” I say, “Well, perhaps it was more than two hours. Would you believe six?” He says, “You’re insane. You’ve lost your equilibrium.” But I say to him, “You believe that the intricacies of this vast cosmos came about just like that, accidentally.” But he says, “Oh, that is different!”

Is it different? Is it? Why, compared to this watch, the universe is ten thousand times of an infinitude more complex and more intricate. The sun and this earth in its orbit around, if the sun were just a little bigger, the earth a little littler, if the earth were a little closer or a little further out, if the earth speeded up just a little, or if it slowed down just a little the whole thing, as we see it, and life itself would be impossible. “Well,” you say, “That’s just an accident. It just happened to be the sun is just so big and the earth is just so big and its movement around the earth is just so fast, just an accident.” Well, I say, “It could be it was an accident. But did you ever think of the moon? It is the same thing about the earth. The earth so big and the moon so big and the weight here and the mass there and the movement of them both? Well that’s two accidents. Maybe that’s two of them. But did you know the eight planets are the same thing? Weigh just so, moving just so in all of their stellar orbits and there are thirty-one moons beside up there. It’s beginning to look as though there were a master plan.

“But I cannot believe in a master plan, for that would mean mind, and mind and a plan would mean God. And I’m a materialist, I cannot believe in God.”

There is a law in physical science called entropy. Entropy refers to the degree of disorder in a system. And one of the basic laws of thermodynamics is this: that entropy in a system tends to increase. May I illustrate it simply? If I have before me a beautiful poem, a beautiful poem and I shake it, I disarrange it; the law of entropy says I will not get out of that disarrangement and that shaking a sublimer poem, but I will get chaos. I will ruin the intent and purpose and meaning and the message of the poem. That law of entropy is in all physical manifestation.

When you apply it to the universe you disturb the universe, and you will not get a more orderly universe, but you will get a more disorderly universe. And that disorder by the law of entropy will increase, and increase, and increase the more it is disarranged and disturbed. “Oh,” but you say, you say, “But time is no factor. And in time,” in English time, in the infinitude of time, “accidents would finally produce this marvelous infinitude that we see above us.”

Well, let’s try it. In its simplest form, let’s take us that same poem. Let’s say Tennyson’s Crossing the Bar and let’s set it up in type. All right you start shaking Tennyson’s Crossing the Bar. Entropy, the law of entropy,entropy begins to work, and the poem is disarranged. But time is no factor. Just keep on shaking. So here I am shaking all the letters and then after a while I look, twilight evening, shake and shake. “Time is no factor,” you say, “keep on a’shakin’.” Shake, and shake, and shake, and shake, for a hundred years; open that box. Sunset and evening, shake and shake and shake and shake, shake for a thousand years; open that box. Shake and shake and shake and shake for a million years; open that box. Shake and shake and shake and shake for ten billion years; open that box. Well I tell you, we’ve got a problem on our hands.

Let’s change that poem to Mary Had a Little Lamb. Now you shake Mary Had a Little Lamb. So we shake and shake and shake and shake. Now you keep on shaking, you just keep on shaking. Oh, we got too hard of a poem! Let’s take one of Mother Goose’s rhymes, “Hey Diddle Diddle, the cat and the fiddle, the cow jumped over the moon.” Now let’s take that one. “The little dog laughed to see such a sport, and the dish ran away with the spoon.” Is that right? You’d know all about that. So we shake and shake and shake and shake and shake, and after he has shaken the letters in that poem for ten billion ions of eternity, it will never come out any kind of a design or an intelligent purpose unless there is somebody who, by will and intelligence, takes those digits and takes those letters in the alphabet and arranges them according to even the simplest poem. Why, my dear friend, a simple poem is like a child’s word compared to the intricacies of this universe. And this is the meaning of that introductory passage in the first chapter of Genesis, “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth” [Genesis 1:1].

Then something happened, and the earth became waste and void and darkness covered the face of the deep [Genesis 1:2]—entropy, the entrance of sin, I think. God created the universe beautiful. Anything that God did would be perfect, and the spheres and their orbits, the Milky Way’s, the chalice of the sky, this planet and every other planet, everything God made was beautiful and perfect. But sin entered, Satan fell, Lucifer fell, and when Satan fell, Lucifer fell, when sin entered, it destroyed God’s universe [Isaiah 14:12].

Sin will destroy anything. It’ll destroy a business. It’ll destroy a nation. It’ll destroy a soul. It’ll destroy a life. It will destroy God’s universe, and it did. And the law of entropy set in and the universe became chaotic and more chaotic and dark and darker and waste and more waste [Genesis 1:2]. And that law of entropy would have continued forever and forever had it not been, “And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the deep” [Genesis 1:2]. And out of chaos, God spake this beautiful world into existence [Genesis 1:3-31]: mind, intelligence.

Oh, dear people, I haven’t…I don’t know where the time goes. Nor have I time to speak of the design in the human body. I come to the conclusion.

The materialist and the end of the world, how does he face it? And how does he describe it? In the existentialist philosophy—which is the modern scholastic background of the academic world—in the seminary theologically, in the pedagogical school where our teachers are trained, in the whole science of government and life—an existential philosophy is the philosophy of despair. There is not any God. There is not any meaning in life. There’s no hope, no future, no destiny. We die as an autumnal leaf drifts to the ground. There’s no resurrection. There’s no immortality. There’s no heaven. There’s no destiny. There’s no future. And our young people, taught the emptiness and the despair of life, turned to unspeakable things, trying to find some way out.

May I point a way? England, “Angle-land”: the Venerable Bede, one of the most dramatic historians and one of the most accurate of all time, told the conversion of the Angles, our forefathers—he was born in Northumbria where they were converted just a few years before the conversion took place—and he described the coming of God’s missionary and preacher, Paulinus, who was sent by the pastor at Canterbury to go to Northumbria, there to present the cause of Christ to the Angles. And King Edwin, of the Angles of Northumbria, is seated at the head of a council table, and his warriors are gathered round and standing round. And at the other end of the table is Paulinus, God’s preacher, presenting the cause of Christ to King Edwin, to his warriors, and to the Angles of Northumbria, our forefathers. When Paulinus had done, his plea for Christ, he sat down. And King Edwin sat at the head of the council table in deep silence. And in that solemn hour one of his warrior sages arose, and addressing the king, said, “Around us lies the black land of Night.” Then he continued:

Athwart the room a sparrow

Darts from the open door:

Within the happy hearth light

One flash,-and then no more!

We see it come from darkness,

And into darkness go–

So as our life, King Edwin!

Alas that it is so!

But if this pale Paulinus

Have somewhat more to tell;

Some news of Whence and Whither,

And where the soul will dwell,–

If all that our darkness

The sun of hope may shine;–

He makes life worth the living!

I take his God for mine!”

[“Edwin and Paulinus: The Conversion of Northumbria,” the Venerable Bede]

And that day King Edwin gave himself to the hope and the promise and the trust in Christ Jesus our Lord. And our forefathers turned from the darkness of paganism to the light of the knowledge of the glory of God that shines in the face of Jesus Christ [2 Corinthians 4:6].

O God, may we not lose what our forefathers have so richly, prayerfully, aboundingly bequeathed to us. Our Lord, in that commitment of life [2 Timothy 2:15], bless us in the work of the day, in the life and the years that lie ahead, in the hour of our death, and in that glorious eternity the Lord hath promised those that love Him [John 14:3], in His faith [Galatians 2:16], in His grace, in His love, and mercy [2 Corinthians 13:14], in His Spirit, in His precious name, amen.

THE

MATERIALIST AND THE END OF THE WORLD

Dr. W.

A. Criswell

Hebrews

11:3

3-23-67

I. Introduction

A. America is becoming

increasingly secular, materialistic

B. Difficult for us to

learn from the past

1. The

emptiness, futility, transitory nature of things material

a. Nebuchadnezzar’s

pride for Babylon (Deuteronomy 4:30)

b. Poem, Ozymandias

C. Philosophy

and worldview of materialism leaves out God

D.

Materialist believes the only reality is physical substance

1. Explain

the beginning as something out of nothing

2.

Explain the ending as disbursement of atoms without purpose

II. The beginning

A. The

watch – parts in a box, shake, you have a watch

1. Same belief about

intricacies of the cosmos

B.

Cannot believe in a “master plan”

C. Basic

concept in physical science is entropy – the degree of disorder in a system

1. Basic law of

thermodynamics – entropy in a system tends to increase

2. Applied to the

universe – becomes more and more disorderly

a.

Put a poem in a box and shake for billions of years, will still not come out

with any intelligent design

D.

Poem is simple compared with the complexities of the universe

1. “In the beginning

God…” (Genesis 1:1)

2. When sin entered, it

destroyed God’s universe(Genesis 1:2)

III. The ending

A. Existentialist

philosophy – no God, no hope, no future

1. Philosophy of

despair

B. Paulinus

preaching to King Edwin

1. Venerable Bede’s

telling of the conversion of the Angles

2. Our forefathers

turned from darkness of paganism to light of God