Freedom Written in Blood

May 31st, 1964 @ 8:15 AM

Isaiah 51:1-2

Related Topics

America, Baptist, Church, Freedom, History, John Clarke, Roger Williams, Separation of Church and State, 1964, Isaiah

Play Audio

FREEDOM WRITTEN IN BLOOD

Dr. W. A. Criswell

Isaiah 51:1-2

5-31-64 8:15 a.m.

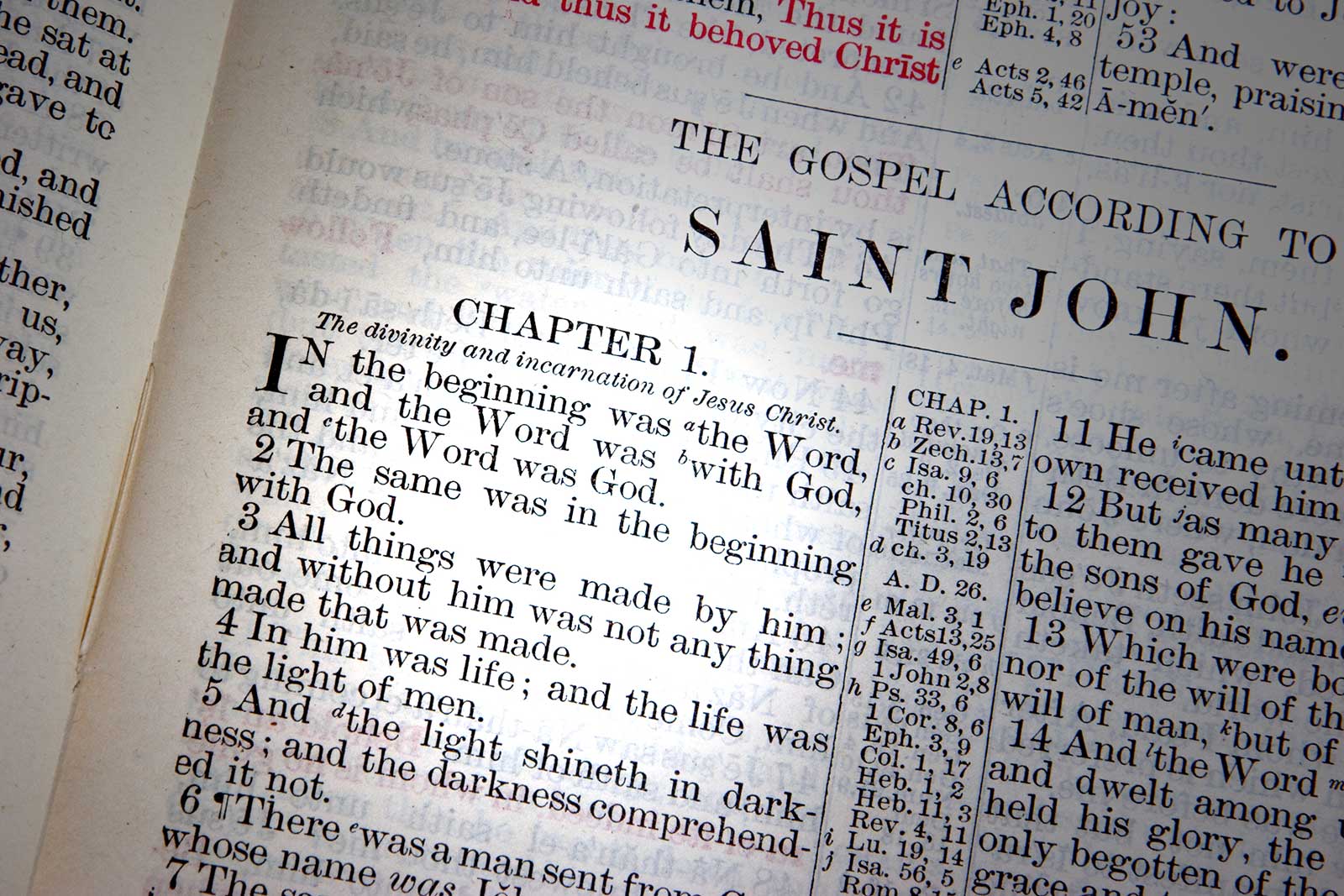

On the radio you are sharing the services of the First Baptist Church in Dallas. This is the pastor bringing the early morning message entitled Freedom Written in Blood. This will be the third, this will be the fourth address that I have prepared on the text and the call of the Hebrew prophet in Isaiah 51:1:

Look unto the rock from whence ye are hewn, and to the hole of the pit from whence ye are digged.

Look unto Abraham your father, and unto Sarah that bare you.

[Isaiah 51:1-2]

The prophet there was calling his people back to a remembrance of the forefathers who planted the foundations for their faith and who made their spiritual inheritance possible. And in keeping with that text, I have been preparing these special addresses on our forefathers who laid the foundations for those spiritual enrichments and heavenly blessings that we enjoy today. This will be the last one that I shall deliver now.

I have one other, and because it so largely concerned an area of life, and government, and denomination, and work in which Dr. George W. Truett was interested, I have decided to deliver it on the Sunday closest to the anniversary of the death of the great pastor. As you know, every year on the Sunday closest to the anniversary of the death of Dr. Truett, I prepare a special address upon some phase of our Christian life and denominational work in which he was vitally interested, and that covers all of them. He was so enmeshed in all of the many faceted lives of our Baptist people. So this coming anniversary, which will be about the fifth of July, the last address will be given. It will be entitled Baptists and the American Constitution.

This morning, Freedom Written in Blood; the last Sunday I spoke here, Sunday before last, the address concerned The Birth of Religious Liberty, and it followed the life of our Baptist people in their struggle in England, and I chose two great Baptist leaders there, John Bunyan and John Milton. And I chose one great Baptist leader in America, Roger Williams. Now today we pick up that thread that lead to the constitution of the state, the colony and the state, of Rhode Island and the gift to the world of its greatest blessing, a gift of our Baptist people, religious liberty.

In 1609 there was born in a country village in the county of Suffolk, England, a lad, a baby by the name of John Clarke. He was wonderfully educated in law, in theology, and in medicine. And he was an M.D., a practicing physician, gaining his medical degree from the University of Leiden in Holland. In 1637 he immigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Remember that Plymouth, founded by our Pilgrim Fathers, was settled in 1620. About six years or eight years later, there was a settlement in Boston. In 1630 it was named Boston. And seven years after the founding of the little settlement of Boston, there came into the village of about one thousand inhabitants this wonderfully fine Englishman by the name of Dr. John Clarke, a theologian and a practicing physician. He brought with him his wife and their little son. He was a magnificent specimen of a man, over six feet tall and wonderfully framed and built.

When he came to Boston in 1637, he saw before him one of the most tragic sights of anyone’s life. When he landed, the churches in Boston, the religious leaders in Boston, were in the act of excommunicating and banishing a great and noble woman. Her name was Mrs. Anne Hutchinson. She was the daughter of an Anglican minister in England. She had married a prosperous, affluent merchant who had come to Boston to make his home. There they fell into a terrible controversy because this noble woman in reading her Bible had come to our Baptist faith.

I have copied from the lips of the minister who excommunicated her and who banished her in Boston. I’ve copied from his lips the words of excommunication and banishment that he said as he stood in his high church pulpit. I quote:

Therefore, in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and in the name of the church, I do not only pronounce you worthy to be cast out, but I do cast you out. And in the name of Christ do I deliver you up to Satan, that you may learn no more to blaspheme, to seduce, and to lie. And I do account you from this time forth to be a heathen and a publican, and so to be held of all the brethren and sisters of this congregation and of others. Therefore, I command you, in the name of Jesus Christ and of the church, as a leper to withdraw yourself out of the congregation.

So Anne Hutchinson and her noble husband and their fourteen children were banished and sent out from the face of civilized man. The husband died not long after, and Anne Hutchinson, this noble Baptist woman, and her fourteen children were massacred by savage Indians. That’s what Dr. John Clarke saw when he came to Boston in 1637. I quote from the doctor as he writes of his arrival in the New World:

In the year 1637 I left my native land, and in the ninth month of the same, through mercy, I arrived in Boston. I was no sooner on shore but there appeared to me differences among them touching the covenants.

Then he describes those differences:

They were not able in those uttermost parts of the world to live together, whereupon I moved, as the proffer of Abraham to Lot, to turn aside to the right hand or to the left. The motion was accepted, and I was requested with some others to seek out a place.

And I’ve quoted from John Clarke what he proposed. Dr. John Clarke proposed quote: “A state,” wherever they could find it to build it, “a state where no constraint could ever be put upon the human conscience, no shackles upon the human spirit, no limit to the freedom of human thought.” So they signed in 1638 what is called the Portsmouth Compact. It was signed by John Clarke who wrote it and by twenty three fellow Baptist leaders. And they in that compact agreed to find a place and to build a state where a man could worship God in freedom and in liberty. They turned northward, but the winter they spent in what is now New Hampshire was so rigorous and severe that they turned southward intending to go to a part of the seaboard that we now know as Delaware.

But on their way down, John Clarke, turning south, John Clarke passed through Providence and met Roger Williams. And Roger Williams persuaded the good doctor and the Baptist theologian; Roger Williams persuaded the beloved physician to stay with him, for he said, “In Narragansett Bay,” and Providence is just at the head of it, “in Narragansett Bay,” said Roger Williams, “is an island,” Aquidneck, “is an island fifteen miles long, three miles wide. And we can purchase it from Canonicus, the Indian chief. And you can build your colony and settle your people there and be close with us.” Dr. John Clarke acquiesced. They bought Aquidneck and named it the Isle of Rhodes, or Rhode Island, and they built two settlements there. One in the north they named Portsmouth. One in the south they named Newport. And the first thing they did in 1640, after settling the island, was to establish a public school; the first public school in the history of the world.

Wherever you find our Baptist people you will find liberty not only in conscience but liberty in education and a devotion to the enlightenment of the soul as well as the mind and the spirit. So the colony began, and after a year or two, Roger Williams and Dr. John Clarke agreed to put their settlements together. And in 1643 Roger Williams won from the commonwealth a charter for the Providence Plantations and for the Isle of Rhodes and made it one colony. And in 1663, under Charles II, after the first charter had been abrogated at the dissolution of the Cromwellian commonwealth, and after the arrival of Charles II to the throne of England in 1660, after twelve years labor, Dr. John Clarke won from Charles II the charter for the colony of Rhode Island. And on the south façade of the beautiful capitol of Rhode Island is a quotation in great letters that I copied as I looked upon that beautiful building. And it is a quotation from that charter: “To hold forth a lively experiment that a most flourishing civil state may stand and best be maintained with full liberty in religious concernments,” the first place in the earth that such freedom was guaranteed to men.

Now we’re going to follow the life of the little Baptist church at Newport, pastored by first Dr. John Clarke, and then by his associate and successor, Obadiah Holmes. In 1639 there came to Salem a sturdy young Englishman who had been educated at Oxford and who immigrated to America with his young wife. He settled in Salem, and he built there the first glass factory on the North American continent. He had an associate, a partner with him who was a Quaker. His name was Lawrence [Southwick]. And because his partner, Lawrence [Southwick], was a Quaker, the religious authorities of Salem arrested him, and tried him, and fined him so heavily that the poor man could never have opportunity to pay the fine. So the court decreed that his two little children should be sold into slavery. Can you believe that in America? Can you believe that on the part of religious authorities? They sold the two children to a rough sea captain with the understanding that he was to take them away, but when time came for the children to be taken away, they so cried and that Quaker partner of Obadiah Holmes so lamented and his wife, until the rough sea captain could not find courage in his heart to separate the family. And he got in his ship and sailed away and left the two children behind.

Obadiah Holmes and Lawrence [Southwick] fled anywhere, anywhere that they might find freedom to live and to worship God. They fled to Newport, to the Isle of Rhodes, to Rhode Island. And there they were baptized into the Baptist Church of Newport by Dr. John Clarke. And they found there that liberty of soul that has blessed us to this present day, and I pray could bless the world and forever. Anyway, there was allowed no other churches in Plymouth Colony or in Massachusetts Bay Colony. So those few scattered Baptist families who lived in these other colonies had their membership at Newport.

Like Wednesday of last week when I was not here, you received into your fellowship, Bill and Anne Coffman, the missionary children of Dr. Woodrow Fuller. There is no Baptist church in the Dominican Republic to which they’re going as a missionary. So they joined this church here, and look forward to the day when a church can be organized in the Dominican Republic. That’s what happened there in Newport. Because no church was allowed to be organized except the state church in the other colonies, the scattered Baptist families held their membership in the Baptist church at Newport or in one of the other Baptist churches in Rhode Island.

Now, in the little city of Lynn which is—Salem’s up here and Lynn’s there, and Boston is there; there’s just three of them up and down that Atlantic seaboard—in the little city of Lynn, there was an aged Baptist member of the church at Newport by the name of William Witter. He was blind as well as aged. So the pastor of the church at Newport to which he belonged, Dr. John Clarke, took with him Obadiah Holmes and John Crandall to visit the aged man and to comfort him in his blindness and in his affliction. They arrived on a Saturday in July in 1651. And the next day, being the Lord’s Day, it was agreed that they would have a little service of divine worship in the home of William Witter, this blind Baptist who belonged to the congregation in Newport, and that Dr. John Clarke would present the message, preach the sermon.

So when the hour came with the little family of William Witter and with four or five strangers who have heard of it and had come to hear the illustrious doctor preach the gospel, while John Clarke was preaching, there burst in upon them two constables who arrested them and put them in jail. And they were arraigned before the court, and I have copied the arraignment. I quote:

For being taken by a constable at a private meeting in Lynn upon the Lord’s Day, and for such things as shall be alleged against them concerning their seducing and drawing aside of others after their erroneous judgments and practices, and for suspicion of having their hands in the rebaptizing—that’s why they called it Anabaptist, baptizing again those who had been sprinkled in infancy—and for having their hands in the rebaptizing of one or more among us.

So they were transported from the jail at Lynn to the prison in Boston, and they came up for trial before the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and his associates. Now I quote from Dr. John Clarke as he writes about the trial in Boston. I quote:

None were able to turn the law of God or of man by which we were condemned. At length, the governor—by the way, I’m about to forget to use my glasses—at length, the governor stepped up and told us we had denied infant baptism and deserved death.

Now may I read that again? Might burn into your conscience; they had denied infant baptism and deserved death. That’s the word of the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to that little group of three Baptist men. And said he would not have such trash brought into their jurisdiction. “Moreover,” he said, “you go up and down and secretly insinuate into those who are weak, but you cannot maintain it before our ministers. You may try and dispute with them.” And when the governor who was sitting as judge said that, Dr. John Clarke at once seized upon the suggestion by the governor, and he welcomed an opportunity to speak of the truth of the Bible with any or all of the ministers in Boston. So it was agreed by the court that Dr. John Clarke should confront the ministers of Boston with these heretical Baptist doctrines. But after the court said it, there was not a minister in Boston that dared face the Baptist preacher on the Word of God. And the debate, the confrontation, was never held.

So they were sentenced to be fined heavily or publicly whipped. The day came for Dr. John Clarke to be publicly whipped. Now he was a learned, and a noble, and a scholarly, and a godly man. So when they stripped him before the state house in Boston, the people, the throng that was gathered around, looked upon him. And one of the men said, “To see a man stripped and whipped who is a scholar, and a gentleman, and reverend divine is more than my eyes can look upon.” And he paid the fine of Dr. John Clarke, a heavy fine. Against Dr. Clarke’s refusal, the court accepted the fine and dismissed it.

Obadiah Holmes was kept in prison until September, and in September he was unmercifully beaten. Now I have copied from the words of Obadiah Holmes as he describes that terrible beating. First of all, friends brought to him stimulants to help him through the awesome ordeal, but he refused. Then he writes—I quote from Obadiah Holmes:

I betook myself to my God that I might communicate with Him, commit myself to Him, and beg strength from Him. I was caused to pray earnestly unto the Lord that He would be pleased to give me a spirit of courage and boldness, a tongue to speak for Him, and strength of body to suffer for His sake, and not to shrink or yield to the strokes or shed tears, lest the adversaries of the truth should thereupon blaspheme and be hardened, and the weak and feeble minded discouraged. And for this, I besought the Lord earnestly. At length He satisfied my spirit to give up, as my soul, my body to Him, and quietly leave the whole disposing of the matter to God. And when I heard the voice of the prison keeper come for me, even cheerfulness did come upon me, and taking my Testament in my hand, I went along with him to the place of execution—now he asked for the privilege to speak to the vast throng of people there, but he was refused; then he continues—and as the man began to lay the strokes upon my back, I said to the people, “Though my flesh should fail and my spirit should fail, yet my God will not fail.” So it pleased the Lord to come in and so fill my heart and tongue as a vessel full, and with an audible voice I broke forth praying unto the Lord not to lay the sin to their charge. And telling the people that now I found God did not fail me and that therefore now I should trust Him forever who failed me not, for in truth as the strokes fell upon me, I had such a spiritual manifestation of God’s presence as the like thereof, I had never felt, nor can with fleshly tongue express. And the outward pain was so removed from me that indeed I was not able to declare it to you. It was so easy to me that I could well bare it yea, and in a manner felt it not although it was as grievous as the spectator said, the man striking with all his strength. When he had loosed me from the post—unchained him—having joyfulness in my heart, and cheerfulness in my countenance as the spectators observed, I told the magistrate, “You have struck me as with roses.”

That’s a famous saying of a martyr who died before him, “Yet I pray God it be not laid to your charge.” Although he describes it that way, for weeks thereafter he had to rest day and night on his elbows and on his knees, for no part of his body could be touched without great suffering; so unmercifully was he castigated by that terrible beating. Then he closes:

Now does it please the Father of mercies to dispose of the matter that my bonds and imprisonments have been no hindrance to the gospel. For before my return, some submitted to the Lord and were baptized and divers were put upon the way of inquiry.

Now, I’m going to follow that last little observation he makes, then I have to close. That public, unmerciful beating of Obadiah Holmes just for the cause that I’ve described to you, sharing in a service in that blind Baptist’s house, that made an impression upon the people of Boston. Two men went up after the beating to shake hands with Obadiah Holmes, and they were fined or whipped just by shaking hands with him. But one of the men who stood there and saw that was named Henry Dunster, the president of Harvard College. And when he saw the stalwart, unflinching devotion of Obadiah Holmes, he turned and in his library picked up his Bible once again, and read, and read, and read from the Word of God, then made the announcement to the Massachusetts Bay Colony that he, the first president of Harvard and their president for twelve years, that he had seen the truth of God and was a Baptist.

The persecution that fell upon Henry Dunster was indescribable. With his family, he was driven out of his house and home that he’d built for him; that he’d built himself, the presidential home of Harvard College. He was driven out in the wintertime. He had a little baby born thereafter whom he named Mary, a little girl. And twice he went through a terrible trial because he refused to have the little baby girl named Mary baptized, sprinkled, as an infant. And soon thereafter, the illustrious great first president of Harvard College died of a broken heart. “Look, look unto the rock from whence ye are hewn, and to the hole of the pit from whence ye are digged” [Isaiah 51:1-2]. It hasn’t hurt us to remember the price our Baptist forefathers have paid that we might live in freedom without molestation, call upon the name of our God according to the revelation of the truth on these sacred pages.

And the glory of our Baptist people is this. What we have sought for ourselves, we have sought for all others of any faith, of any denomination, of any creed, of any kind, that nowhere in this earth a man might be hurt, or molested, or imprisoned, or martyred because of his faith in God. The Lord bless this superlative, supernal gift of our Baptist people to the nation of America, to the conjoined nations of the earth, and to all mankind now and forever, amen.

Now while we sing our hymn of appeal, on the first note of the first stanza, somebody you giving your heart in public trust to Jesus [Romans 10:9-10], would you come and stand by me? A family you, a couple, as God shall open the door and lead in the way, make it now, make it this morning’s hour, while we stand and while we sing.