THE PASSION FOR SOULS

Dr. W. A. Criswell

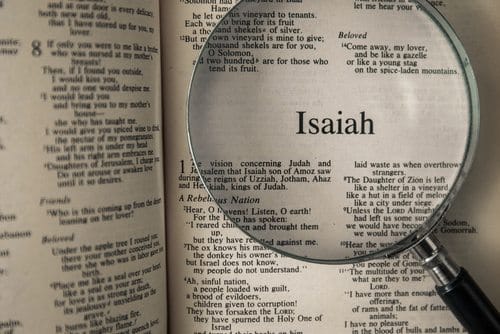

Isaiah 6:8

4-6-75 10:50 a.m.

The title of the message this hour is A Passion for Souls. And we welcome you who listen on radio and watch on television the First Baptist Church in Dallas, and this is the pastor speaking from a text in the sixth chapter of Isaiah. In the last Sunday service, I saw the exposition of the chapter as a whole [Isaiah 6:1-13]. Today we shall speak of one text in it, verse 8 [Isaiah 6:8]. The sixth chapter is a record of the call of the young prophet. In the year that the great king Uzziah died: “He saw the Lord who never dies, seated on His throne, high and lifted up, and the train of the Lord filled the whole earth. And the seraphim cried one to another, Holy, holy, holy is the triune God” [Isaiah 6:1-3].

And in the presence of the Majesty on high, the young man cried saying, “I am undone. Woe is me! for I have seen the King, the Lord of hosts” [Isaiah 6:5]. And one of the seraphim took a live, burning coal from off the altar, and the altar is ever a symbol of the judgment of God upon sin. It is a symbol of the cross, of the sacrifice of Christ that we might be washed. He took with a tong a burning coal from off the altar and laid it on the lips of the young man saying, “Your iniquity is pardoned. Your sin is forgiven” [Isaiah 6:6-7].

It was then that he heard a great voice from the throne of God saying, “Whom shall I send, and who will go for Us?” And he answered, “Here am I, Lord; send me” [Isaiah 6:8]. And the Lord sent him. “Go, and tell.” And the message was, “They will not hear, and they will not soften their hard hearts, lest they be converted and be saved” [Isaiah 6:9-10].

But some of them will hear, and some of them will listen, and some of them will turn, and some of them will be saved; the doctrine of the remnant. Not everyone will believe, but some will always believe. Not everyone will turn, but some will always turn. Not everyone will open hearts to God, but some of them always will. And the young prophet gave himself as a volunteer to be that messenger and that preacher: “Here am I, Lord; send me” [Isaiah 6:8]. And it gave rise to the subject of the message, A Passion for Souls.

I speak first of the minister, the pastor of the church, and his fellow elders. Said an old Puritan divine:

I marvel how I can preach stolidly and coldly, how I can leave men in their lost condition and that I do not go to them and beseech them for the Lord’s sake, however they take it and whatever pains or trouble it should cause me.

When I come out of my pulpit, I am not accused of want of ornaments or elegance, nor of letting fall an unhandsome word, but my conscience asketh me, ‘How could you speak of life and death with such a heart? How couldst thou preach of heaven and hell in such a careless and sleepy manner?’ Truly, this peal of the conscience doth ring in my ears, O Lord, do that on our own souls, that Thou wouldst use us to do on the souls of others.

Dr. Andrew Bonar listened to a preacher who was speaking with great zeal and thunder. And when the service was over, he went up to him and said, “You like to preach, don’t you?” And the man replied, “Yes, indeed I do.” And Dr. Bonar asked him, “But do you love the souls of the men to whom you preach?” It is a far cry and a vast difference between preparing a sermon or organizing a church or propagating a program, and loving people, trying to get them to God, trying to win them to Jesus, loving their souls into the kingdom and burdened for the lost among us.

When I was growing up, there was a mighty, to me, mighty minister of Christ by the name of Lee R. Scarborough. He was an evangelist in heart, called to be president of our seminary in Fort Worth; he built there what he called a chair of fire. I would listen to him as a student in Baylor, as a young seminarian, and as pastor of a church. I never heard him, I never listened to him but he moved my soul. Not that he was brilliantly eloquent, not that he was elegant or dramatic in delivery, but the man’s heart, the man’s soul yearned for the lost. And when he preached, he pressed the appeal for men to be saved.

I remember, as a student in Baylor, my roommate was ordained to the gospel ministry in the Travis Avenue Baptist Church in Fort Worth. And he had me go with him from Waco to Fort Worth to deliver the charge at that ordination service. And in that hour of ordination, Dr. Lee Scarborough prayed the ordaining prayer, and he prayed in the prayer this, “O God, remember that homeless, prodigal boy that I picked up today on the streets of Fort Worth and who is now in my home to rest and to sleep for the night. Dear God, help me to win that homeless and prodigal boy to Thee before he leaves our home.” As I listened to the prayer of the president of our seminary, it was hard for me to realize that this great, glorious man had somewhere on a street in Fort Worth picked up that homeless boy, took him with him to his own house, and now was praying that as he shared the family dinner, and as he slept under the roof of the home during the night, that God would help him win the boy to Jesus.

Dr. Truett, the far-famed pastor of this church for forty-seven years used often to say in every sermon, “There ought to be the seeking note.” And using that phrase several times, it stayed in my memory, “the seeking note.” Whatever the message is entitled, wherever in the Book it is preached, there ought to be in the sermon a pull, a tug at a man’s heart to give himself to Jesus.

This last week I was in one of the great, great cities of America, our second largest city, and I spoke for hours to a company of pastors brought together in convocation in that city. And one of the things that I pled for was that every time that the man preaches, preach for a verdict, reach toward the decision, make an appeal, extend an invitation and believe that God will honor it, that He will give you souls. And some of the men in, in an assigned part of the convocation for questions, some of the men said, “How do you do that? What do you say? And if somebody were to come, what would I do with him?” My reply was such as you’re so familiar with. “My brother, do it in the same way as a salesman would ask a man to buy the car that he’s offering, or buy the insurance policy that he’s explaining, or buy a piece of merchandise in the store. Do the same thing.”

We have something to sell, if I could call it like that. We have the best article in the world to offer if we could say it like that. We have the finest insurance policy in the earth, man forever and ever. Just as you’d make an appeal for a man to take something, to buy something, to have something, make an appeal for a man to take Jesus, to open his heart to the Lord, to say yes to Christ. And then when he comes forward, rejoice, rejoice, pray with him, talk to him, read the Scriptures with him, just be glad all over the place that the Holy Spirit has honored the appeal, and then follow it through the rest of his life in the communion and fellowship of the church.

But I said to the men, “Most of all and above all, how it will change your own soul and your own ministry, your own preaching, if in it, always there is that praying to God, ‘Lord, today give me a harvest. Give me souls.’ It’ll turn every word that you say, every gesture that you make, the very sound of your voice, if you know that you are standing there in the presence of God and men and angels to make an appeal for the lost”; the passion for souls.

May I speak now about you? Someone asked me in one of those convocations about the Holy Spirit and about attending the services. And I said, “This is a part of the will of God for our lives. We are the temple of God. Each one of us is a house of the Lord [1 Corinthians 6:19]. That is the Pentecostal difference.” In the old covenant, the Spirit, the presence of God was housed in the tabernacle, and in the temple, the shekinah glory of God [Leviticus 16:2; Numbers 7:89], but at Pentecost, the Holy Spirit found a new house and a new home. He is tabernacled now, He is templed now in the hearts of the believer. Our body is a temple of the Holy Ghost [1 Corinthians 6:19]. And He has another house. He has another temple, and that temple is the sanctuary of the Lord when God’s people gather together in His name [1 Corinthians 3:16-17].

And what is the power of that convocation? It is simple. When I bring the Holy Spirit with me in my heart and you bring the Holy Spirit with you in your heart and we’re here together in this church by the thousands, there is a power in it! There’s a moving in it! There’s a glory and a praise in it that is sometimes too deep for tears. Our hearts just overflow. It is the presence of God in the service. And that’s why all of us have a vital and a vitally significant, meaningful part in coming to the house of the Lord. We’re not just traipsing here, not lightsomely assembling here. We are coming in God’s name, for God’s purpose, with an intercessory prayer in our souls that God will use me and every part of the service to win somebody to Jesus.

For us to come to the house of the Lord indifferently, casually, summarily is unthinkable! It is impossible to the real child of God. Oh, how meaningful thus to come! Emerson one time said, “Things are in the saddle and they ride mankind.” You know, when I read that, I thought, “I wonder what Emerson would say today, Ralph Waldo Emerson would say today.” He said that, “Things are in the saddle and they ride mankind,” he said that before there was an automobile, before there was a radio, before there was a television, before there was a picture show, before there was anything that we know today that press against the attention, commanding the thoughts of the whole world.

I wonder what Emerson would say today. Things, things, we live in a fury of them. Our minds are consumed by them, and we are so feverish in our restlessness that if we’re not entertained or we’re not looking at an idiot box or if we’re not on the way rushing somewhere, we are miserable and unhappy, all of which is a repercussion of the spiritual sterility and emptiness of our souls. Oh, to push them out, out, out! I don’t need to be entertained. I can have a wonderful day with God; don’t need to be taken somewhere. I could have a marvelous session with Jesus, unhurried and unfeverish, quiet in the Lord, unafraid, living in infinite confidence in Him and loving God’s people and loving the lost for whom Jesus died [1 Corinthians 15:3]. What a wonderful way if I could be like that!

You know, sometimes I think we hardly recognize the faith in us compared to the Christian religion as it was in the days of the apostles and the first missionary evangelists. They were so zealous, and we are so phlegmatic. They were so eager, and we are so cold and dead. They would weep over a city, such as Paul says weeping over Ephesus from house to house with tears, testifying, repentance toward God and faith in our Lord Jesus Christ [Acts 20:31, 19-21]. I doubt whether seldom we ever even weep over ourselves. O Lord, that the spirit of compassion and intercession might fall upon our congregation; the passion for souls to remember the lost, to pray for them and to say a good word for Jesus every opportunity that we have.

In one of the great churches of the South, I was holding a revival meeting, and at the ten o’clock morning hour, I spoke on praying for the lost, a burden for the lost. And after the service was over, I was standing in front of the pulpit and surrounded by people who were talking to me, most of whom were graciously kind, saying how they were happy I was there and how they were blessed by the message. And while I was standing there, a man made his way and stood immediately in front of me; he was a tall, skinny man with a long, bony finger, with a great big black Bible under his arm like that. He took his stance solidly in front of me, and with his long, bony finger, he punched my nose almost. He put it right there in my nose, and he said, “You are not a New Testament preacher!”

“Well,” I said, “I thought I was.” What, what made him think that I was not a New Testament preacher?

He said, “Well, I came here to hear you this morning, and you’re not a New Testament preacher. I heard you preach this morning about praying for the lost and being burdened for the lost.” He took out his Bible from under his arm and held it there in front of my nose and said, “Show me in this Book where it says we’re to pray for the lost and be burdened for the lost.”

“Well,” I said, “It’s just all through the Book.”

“Well,” he said, “Give me chapter and verse where God says we’re to pray for the lost.”

“Well,” I said, “Fellow, I’m embarrassed, but somehow right at this moment I can’t cite you chapter and verse.”

He drew himself up to his long, bony, skinny height, put his finger back in my face and said, “Isn’t that what I said? You’re not a New Testament preacher!” And he turned triumphantly on his heel and stalked out of the church and left me there in the midst of my admirers.

Had there been a trapdoor to open in the floor, I would have been grateful for it, just to fall out of sight. Oh, they took me to my hotel room; I closed the door; I sat down in a chair and buried my face in my hands and said, “Dear God, is that not right? Is that screwball correct? There’s nothing in God’s Word about praying for the lost?” I had one of those strange experiences that you’ll have once in awhile. As I cried that prayer, “Lord, is there nothing in the Word, praying for the lost,” the Lord came down into that room and put His hand on my shoulder—it seemed that real—and said to me, “Why, preacher, did you never read in My Holy Word, Romans chapter 10, verse 1? Brethren, my heart’s desire and my prayer to God for my lost people is that they might be saved” [Romans 10:1]. And then chapter 9, “I could wish that myself were accursed from Christ for my brethren, my kinsmen according to the flesh”[Romans 9:3]. “My heart’s desire and my prayer to God for my people is, that they might be saved” [Romans 10:1]. Or as Jeremiah cried, “Oh that my head were waters, and mine eyes a fountain of tears, that I might weep day and night for the lost of the daughter of my people!” [Jeremiah 9:1]; a passion for the lost.

For a man to be consumed with a great passion is not something new. In that far ago day, back there in the days of Christ and before, and of Paul and before, why, there are men that every schoolboy is conversant with. Consumed by a passion for military conquest was Magnus Pompey. Consumed with a passion for power was Julius Caesar. Consumed with a passion for praise and flattery was Tullius Cicero. Consumed with a passion for tradition was Porcius Cato. Consumed with a passion for pleasure was Mark Antony. Consumed with a passion for money was the other triumvirate, Aemelius Lepidus. But in those days came a man so different. Consumed with a passion for the lost; “Jesus, moved with compassion,” His ever, His enduring name [Matthew 9:36, 14:14, 15:32]. “I have compassion on the people” [Mark 8:2]. And He preached the gospel of the kingdom to the poor, and He healed their illnesses and bear their sicknesses [Matthew 11:4-5]. And that spirit of intercession and burden for the lost of the people was in every one of His apostles and His disciples. And it ought to be in us today.

In the moment that remains and our time is gone, I want to point out to you, in just a moment, how that is. Erasmus was an intellectual beyond compare. No one dared challenge his supremacy. He was elegant, he was learned, he was brilliant, he was polished. But it was not Erasmus whose heart was moved for God and for the people, it was rough, big, crude, rude Martin Luther! And when a friend of Martin Luther asked Erasmus who said he believed in the principles espoused and championed by Luther, when a friend of Luther asked Erasmus to stand by him, Erasmus replied, “Shall I lose my living and lose my head?”

God used the man who loved the people, Luther. May I cite just one other? You had two men together one time when England was facing a bloody revolution. The revolution of France literally bathed that nation in blood, the French Revolution. A like revolution was coming from the masses of the downtrodden and the poor. A like revolution was coming in England, and there were two men who stood side by side. One was Sir Horace Walpole, and the other was George Whitefield.

Whitefield grew up in a saloon, in a tavern, and he, he knew nothing in the days of his youth but the seamy, sordid side, the gutter side of humanity. Sir Horace Walpole grew up in a duke’s home, the heir of a great fortune. And looking out over the tragedy of England in that day, Horace Walpole listened to Whitefield, was moved by him, turned to his cynical, sarcastic, luxury-loving life, just looking at the whole world as it lay in tragedy and trouble with supreme, consummate indifference, Sir Horace Walpole.

George Whitefield, oh, I wish I could have heard the sound of that man’s voice. David Garrick, the great English actor, said, “Oh, that I had his voice and his dramatic gestures.” David Garrick said, “He could pronounce the word of Mesopotamia and bring me to tears.” John Newton, who, who wrote “Amazing Grace,” John Newton said, “I don’t know who is the second great preacher in England, but I know who’s the first, George Whitefield.”

When George Whitefield was preaching in Philadelphia, Francis Hopkins and Benjamin Franklin went to listen to him. They had heard that he makes an appeal for money for the Lord, so Francis Hopkins said, “I am going to leave everything I have at home so I can’t give anything.” And those two men stood there and listened to Whitefield. And Benjamin Franklin, as he heard him, resolved first, “I’ll give him my coppers.” And as Whitefield continued, Benjamin Franklin said, “I’ll give him my silver.” And then as he continued, Benjamin Franklin said, “I’ll give him my gold.” And when finally the collection was taken, Benjamin Franklin gave everything that he had. And Francis Hopkins, the great legal jurist and essayist, having left everything at home so he wouldn’t give, listening to George Whitefield, he turned to a neighbor and said, “Neighbor, lend me some money. I have to give.”

A preacher whom I do not know, his name is Cooper, when George Whitefield preached to a crowd of thirty thousand on Boston Commons, a pastor in Boston said, “In the week that followed, I had more men and women come to me burdened for their souls than in all the twenty-four years of my ministry before me.” O God, that I think is what it’s all about. Our elegance may find its order, and our academic training may be something that is modern day required, and the beauty of our worship services, I am sure, always acceptable to God that it may be done decently and in order [1 Corinthians 14:40], says the Book, but O Christ in heaven, where’s the heart, and where’s the pull, and where’s the appeal, and where are God’s lost and wayward children?

I must close. On the cenotaph of George Whitefield, they carved a flaming heart. John Calvin’s coat of arms was a hand lifting up a burning heart to God. O Lord, that it might be thus with us, our hearts burn within us. It’s a prayer that God will give us souls. And it’s our daily intercession that the Lord will use us this day to speak some good, humble, precious word for Jesus. May the Lord honor it this morning.

In a moment we stand to sing our hymn of appeal, and I’ll be standing right here on this side of our Lord’s Supper table. Out of the balcony, with time and to spare, would you come? A family, a couple, or just you, in the press of people on this lower floor, into the aisle and down to the front, “I’ve decided for Christ and I am coming today.” The whole family, the wife, the children, or just you, make the decision now in your heart, and in a moment when we stand to sing, on the first note of the first stanza, come walking down that stairway or walking down that aisle, “Here I am, preacher, here I come,” while we stand and while we sing.