God and the Reasoning Mind

January 18th, 1981 @ 10:50 AM

Acts 17:2

Related Topics

Apologetics, God, Ransom, Resurrection, Theology, Great Doctrines of the Bible: Theology, 1981, Acts

Play Audio

GOD AND THE REASONING MIND

Dr. W. A. Criswell

Acts 17:2

1-18-81 10:50 a.m.

It is a privilege and one for which we are never forgetful that God gives us our radio and our television and that we have opportunity to speak the name of our Lord to you; some of you in a home; some of you in an office. On the radio, some of you driving along in a car. This is the First Baptist Church in Dallas, and this is the pastor bringing the morning message entitled God and the Reasoning Mind.

In the long, long series on theology, “The Great Doctrines of the Bible,” divided into fifteen sections, last Sunday morning we finished the section on the Bible, bibliology. And today we begin the series of seven messages on theology proper, on the doctrine of God. It will continue through the last message entitled “The Unfathomable Mystery of the Trinity.” And it begins today with God and the Reasoning Mind.

One of the characteristics of the apostle Paul as Dr. Luke watched him, worked with him, followed him, journeyed by his side; one of the characteristics of Paul as Dr. Luke writes it in the Book of Acts is that he reasons. He will be reasoning in the agora. He will be reasoning in the marketplace. He will be reasoning in the synagogue. He’ll be reasoning as he stands before the Roman procurator, Felix.

Now as a background, look at it with me. Turn in the Book of Acts to chapter 17, chapter 17 in the Book of Acts [Acts 17]. It begins, and Paul came with his company to Thessalonica, the capital of the Roman province of Macedonia. “And Paul, as his manner was . . . reasoned with them out of the Scriptures” [Acts 17:2], opening and alleging; in Thessalonica, reasoning out of the Scriptures. The majority of that chapter is given to his address in Athens [Acts 17:16-34], to which we shall return. Now chapter 18 of the Book of Acts, “After these things Paul departed from Athens, and came to Corinth” [Acts 18:1]. Now look at verse 4, “And he reasoned in the synagogue every Sabbath, and persuaded the Jews and the Greeks” [Acts 18:4]. Now look at verse 19 in the eighteenth chapter of Acts, verse 19 [Acts 18:19], “And he came to Ephesus . . . and reasoned with the Jews” [Acts 18:19]. Just once again, turn to the twenty-fourth chapter of the Book of Acts, Acts chapter 24. Now follow verses 24 and 25 in chapter 24 [Acts 24:24-25]:

After certain days, when Felix came with his wife Drusilla, who was a Jewess—

she was the sister of Herod Agrippa II—

he sent for Paul, and heard him concerning the faith in Christ.

And as Paul reasoned of righteousness, temperance, and judgment to come, Felix trembled, and answered, Go thy way for this time; when I have a convenient season, I will call for thee.

[Acts 24:24-25]

I have often wondered what Felix thought he would hear when he called for the apostle Paul, and stood before him. What did he think he would listen to? Some far-out unimaginable, unlikely portrayal of what some superstitious mind might be able to describe? Follywide the mark, such an expectation of that; the Scriptures say Paul reasoned—reasoned, dialegō—of righteousness, temperance, and judgment to come [Acts 24:25]. God and the reasoning mind; it is a part of us, the way we are made, that we seek an answer.

Plato, concerning Greek rationality wrote this sentence: “A man must attempt to give an account of things because he is a man, not merely because he is a Greek.” However the characteristic of the Greek was to probe, to inquire, to philosophize, Plato says that is not just a characteristic of a Greek, it is a characteristic of a man. Our hearts seek and demand an answer. And not only is that a characteristic of us, we seek answers, and they have to satisfy us somehow. But others ask questions of us. And we ought to have an answer for them. I do not think it is right that we sneer at the arguments and questions of the humanist, or the materialist, or the secularist, or the infidel, or the atheist. We ought to answer. Nor do I think it is right for us to ignore these who have doubts and questions in our own midst.

Some people are surprised to learn that I sometimes am overwhelmed by doubts and that I seek an answer in the mind of God. This is not away from the will of our Lord. Simon Peter wrote in the third chapter of his first epistle, verse 15: “Be ready always to give an answer to every man that asketh you a reason for the hope that is in you” —do it “with meekness and with fear” [1 Peter 3:15]. And all of us are acquainted with that third verse of Jude [Jude 1:3]. He says to us: “earnestly contend”—euaggonizomai—agonizingly so. Not peripherally, or indifferently, or superficially, or summarily so, but agonizingly so—“contend earnestly for the once-for-all delivered-to-the-saints faith” [Jude 1:3]. That is an unusual word. All of that is one Greek word: “contend earnestly for the once-for-all delivered-to-the-saints faith.” It is in the will of God this seeking an answer that is rational and intelligent, appropriable and acceptable.

God made us free in our minds and hearts and wills and souls. He did that in the beginning with our first parents. Out of all that lay before them, they had choice [Genesis 2:16-17]—freedom of volition, spirit, will—and that freedom of mind, of soul, cannot be denied us. You can coerce, and you can imprison and incarcerate my body; but you can’t my mind. There is a part of a hymn—

Our fathers chained in prisons dark

Were still in mind and conscience free—

the rest of the quatrain—

How blessed would their children be,

If we, like them, could die for Thee!

[“Faith of Our Fathers”; Frederick W. Faber]

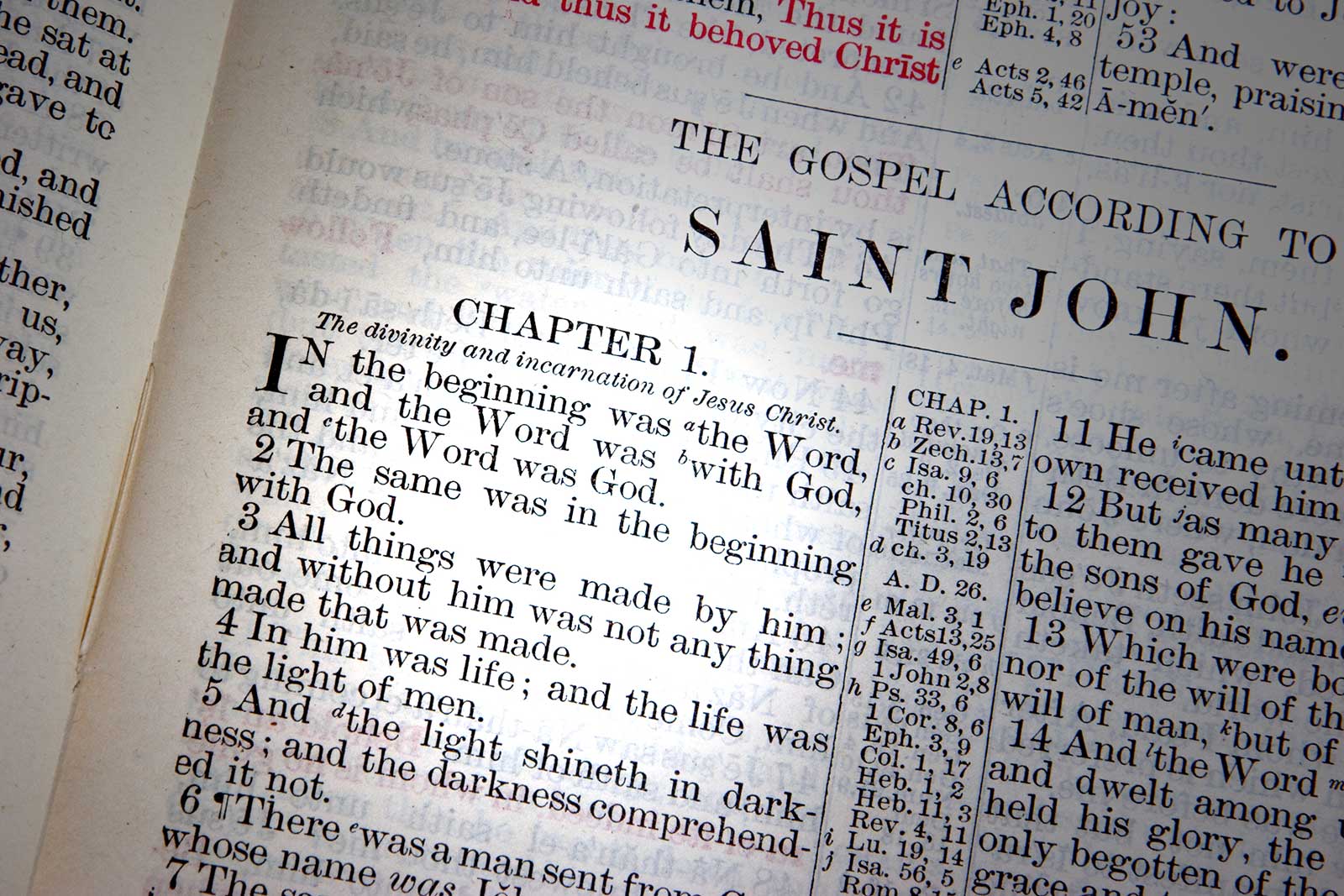

You may imprison my body, but not my mind. My mind is free! What a powerful weapon, therefore, does God give us in persuasion, not in coercion, but in reasoning. For if I can win a man’s mind and his heart, I have the whole man. That is why I think God addresses His gospel message to the mind, and to the heart, and to the soul. God is truth. And He revealed Himself in someone that John 1:1 calls the reason of God, the mind of God, the intelligence of God, the thought of God. That’s the most astounding of all of the philosophical—and it is philosophical—sentences in human literature: En arche ēn ho logos, kai ho logos ēn pros ton theon, kai theos ēn ho logos: “In the beginning was the Word,” the reason, the mind, the intelligent activity of God. And reason, mind was pros ton theon, face-to-face with God. And theos, God was the reason, the mind, referring to the Lord Jesus Christ. It is an astonishing thing and an amazing thing, when you look carefully—not superstitiously or sneeringly or ridiculingly at the Word of God. It is a marvelous thing that God addresses His message to the intelligence of the man. “Look! See! Handle! Judge for yourself!” It is an intelligent and reasonable gospel. And it is reasonable to be a Christian.

So we come in this midst of Paul’s reasoning at Thessalonica, reasoning at Corinth, reasoning at Ephesus—we come to his address to the university center of all of the ancient world—even at Athens [Acts 17:16]. So he stands there before the Areopagus [Acts 17:19]. That’s the supreme court of Attica, the capital city of Athens. And as he stands in the midst of those learned and gifted Athenians, you will never find sculpture that will excel them. You will never find drama that will excel them. You will never find literature that will excel them. You will never find poetry that will excel them. You will never find philosophy that will excel them. And the science we know today is just an extenuation of what they discovered then. He stands there in the midst of that university center of Athens and delivers his reasoning and reasonable address [Acts 17:16-17].

Now as he stands before the populace, the pagan polytheists would have no trouble accepting this “new god”—they call it—that Paul was preaching. For it says that as Paul stood there, they were very enticed by his preaching to them concerning these new gods; because Paul was preaching Iesous—that’s male—and Anastasis—that’s female; Jesus and the resurrection. They had been acquainted all their lives with pairs of gods. There is Jupiter or Jove and Juno. There is Venus and Osiris. Oh, they were all paired! So when he came, they were intrigued by Iesous and Anastasis, new gods they had never heard of before. And they would have had no trouble accepting them. They would have added Iesous and Anastasis to Jove and Juno, and Isis and Osiris. The only thing was Paul was preaching we ought not to think of the Godhead in pairs like that—like they were made out of gold or silver or stone graven by art and man’s device [Acts 17:29]. Paul says this is without knowledge [Acts 17:22-23]. And God in the past has overlooked it; but now commandeth all men everywhere to turn [Acts 17:30]. Pagan polytheists would have had no trouble accepting two more gods. It was just the exclusiveness of Jesus alone as being the one true living God that troubled them.

Now the other group that he had there were of an altogether different sort. They were something in another world. They were the philosophers. And the philosophers were just like you. They scoffed at gods made out of stone and wood, graven by man’s device. All of those mythological characters that were supposed to live on Mt. Olympus, that are described in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and all of the dramatic literature of Euripides and Aristophanes and Sophocles—all of that was idiocy to them, just as it is to you. Those philosophers to whom Paul was preaching were materialists of the first order. And they were atheists of the deepest stripe and color. They were materialistic atheists and they were atheistic materialists. And two of them—two of the groups are named here. “Certain philosophers of the Epicureans, and the Stoics, encountered him. And some said, What is this spermalogos, this seed picker talking about?” [Acts 17:18]. “What would he say if he had anything to say?” Now, that is an interesting confrontation between these university men, the most learned of the age, the Epicureans and the Stoics and the apostle Paul; God of the reasoning mind.

Those Epicureans, long time ago—dying in 370 BC, there was a Greek philosopher named Democritus. And he propounded a theory of the universe that is compelling indeed. In the Greek there is a word temno which means to cut. So tomos an adjectival form of it means “cuttable, divisible.” Now they put an alphaprivative in front of it and make it atomos, atom—and atom means something that is “uncuttable, indivisible,” an atom. Now Democritus propounded the philosophical explanation of what we see as being this: everything is made out of atoms—these whirling, jostling particles—and they differ only in size and weight and refinement.

Democritus taught that the finer of the atoms made up the soul of a man, and the coarser of the atoms made up the material world around us. In life the atoms came together. In death they were dissolved and scattered. So they combined in living form and then lost their combination in death. And the whole universe is made up of these uncuttable, indivisible particles that he called—atomos, uncuttable things, indivisible things—“atoms.” Epicurus, who died exactly one hundred years after Democritus—he died in 270 BC—Epicurus took that materialistic philosophy of Democritus, and he propounded his world view upon it. All life is nothing but a gathering together of atoms, has no meaning, has no purpose. Therefore, taught Epicurus, we ought—in the brief little span of our lives—we ought to get the most out of it that we can. Let’s be happy. Let’s be joyful. Let’s get all of the pleasure we can wring out of it. And their famous sentence, “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die.” That is the philosophy of Epicurus.

Now Zeno was no less materialist and atheist. Zeno taught—Zeno died about six years after Epicurus—Zeno taught on the stoa, the porch. And his philosophical school came to be known as the Stoics. Zeno taught that God is the world, and the world is God. He is a pure pantheist. Pantheism is that the universe is God. Now out of that philosophical foundation he drew the conclusion that the highest joy and privilege and pleasure of the man is to yield himself to the providences of life. Don’t fight against them. Accept them. And there we came into the word “stoical”—the man who accepts any providence in life as being unmoved is stoical; the grace and virtue of fortitude. But the basic teaching of Zeno and his Stoics, and Epicurus and his Epicureans—the basic teaching is always materialistic and atheistic. Paul standing before those university men, and the polytheists that gathered around them, Paul preached a message of an altogether different character, of a different sort, of a different kind. Paul reasoned with them concerning a message in a different world. Paul is speaking of a personal, living, reality God whom we can know, and feel, and touch, and worship, and adore, and serve—a personal, living God.

And as he presents his message, he first of all will declare what I think is a universal truth; namely, the human heart witnesses to the reality of a personal and living God. Paul does it like this. ”As I passed by, I beheld your devotions, and I found an altar with this inscription, TO THE UNKNOWN GOD. Whom therefore ye worship agnoountes, “not knowing,” Him declare I unto you” [Acts 17:23]. For He that made us—made us so that we “should seek the Lord, if haply we might feel after Him, and find Him . . . for in Him we live, and move, and have our being” [Acts 17:27, 28]. Not far off, and certainly not a graven image, but a God who is nearby and close, who has placed in our hearts the desire to seek Him and to find Him? “For in Him we live, and move, and have our being” [Acts 17:28]. All of the philosophies of the world cannot stifle the instinctive hunger and cry of the human heart for God. It is a universal appeal.

When I was lying there at home waiting for God to give me strength to come back to the pulpit, exactly one year from now, I read for the first time Augustine’s Confessions. And in the first paragraph there was a sentence that I have heard quoted more than any sentence in literature, “O God, Thou hast made us for Thyself, and we are restless until we rest in Thee.” There is a universal hunger for God that we cannot drown, and we cannot stifle. Will Durant, formerly chairman of the Department of Philosophy at Columbia University and the author of that world famous book, the history The Story of Philosophy, wrote:

God who was once the consolation of our brief life and our refuge in bereavement and suffering has apparently vanished from the scene. No telescope, no microscope discovers Him. Life is become in that total perspective which is philosophy, a pitiful propagation of human insects on the earth. Nothing is certain in it except defeat and death, a sleep from which it seems there is no awakening. Faith and hope disappear. Doubt and despair are the order of the day. It seems impossible any longer to believe in the permanent greatness of man or to give life a meaning that cannot be annulled by death. The greatest question of our time is not communism versus individualism, not Europe versus America, not even East versus West. It is whether man can bear to live without God.

Universally, the instinctive cry of the human heart for God and all of the advancement we have made in the tools and gadgetry of science does not change it. And all of the course in power of a government like Communist Soviet Russia is not able to crush it out. It stays in our hearts forever, this seeking and longing and searching after God.

Now my own reasonable deduction: could it be, is it possible that we have that longing in our hearts for God only to be mocked and ridiculed and derided? Is it there to crush us and to bow us into the dust in defeat and agony? Is that why it’s there? If it is, that is the only instance in God’s universe that is there without reason and without purpose and without design. Everything we see in the universe has a reason and an intelligent design and purpose back of it—everything. If we had hours here, we would discuss it.

The earth, swinging around that central sun, if it swung in its path just a little slower it would be pulled by gravity into the sun. As it goes around the earth, if it were just a little faster it would lose its orbit and be flung out into space. It swings just right. The design is just perfect that it stays just so. If it were just a little nearer the sun, we would burn up. If it were just a little farther from the sun, we would freeze to death. It swings in its orbit just so. There is purpose and design in what God has done. The whole universe is like that. There is reason, intelligence, purpose back of everything that we see. The fin of a fish has a purpose. The wing of a bird is designed for a reason. The hoof of a horse is made for just that purpose; the hand of a man. Shall I not also say that God placed in our souls a hunger for Him? And He did it with a design, with a reason, with a purpose. Paul says it is there that we might seek the Lord, that we might feel after Him, that we might find Him [Acts 17:27]. “For in Him we live, and move, and have our being” [Acts 17:28]; God and the reasoning mind. The human heart testifies to the reality of God.

In the few moments that I have left—can you believe I have been preaching over thirty minutes? It seems to me when I stand up here to preach, I just get started and that confounded good-for-nothing clock goes around there to twelve. That’s why I say, we’re going to have us a Criswellian planet one of these days. And all who want to see me mount a soapbox and preach forever with no clock, no time, you’re invited to come.

God and the reasoning mind, the human heart, and the greatest of all of the confirmations: the revelation of God in Christ Jesus. “He that hath seen Me hath seen the Father” [John 14:9]; the knowable God, the touchable God, the personal God, the living God, the incarnate God, Jesus our Lord. The one great incontrovertible fact of all time and all creation is Jesus our Lord. The world cannot bury Him; the earth is not deep enough for His tomb. The clouds are not wide enough for His winding sheet, and the rocks are not big enough to cover the grave. He arises, He lives, He ascends into heaven, but the heaven of heavens cannot contain Him [2 Corinthians 2:6]. He lives like a bush burning unconsumed [Exodus 3:2] in His churches and in our hearts as we walk with Him and talk with Him by the way. He stands midmost in human history, in the life of the ages. Like some great towering mountain Jesus looms in the earth, the farther slope reaching back to the creation and the beginning of time, and the hither slope reaching toward the great consummation of the ages. The eyes of those in the days past look forward to Him with prophetic gaze, and we look back to Him in historic faith. He stands in the center of history. Before him it is BC, “before Christ.” After him it is anno Domini, “in the year of our Lord.” The very place where He was born and where He died is the center of the universe. All of the nations on the west write and read from left to right toward Him. And all of the cultures and nations on the other side in the east, read and write from right to left; centering in Him.

And He is the manifestation of God [John 14:7]. Colossians 1:15: “He is the image of the invisible God.” Colossians 2:9: “In Him the fullness of the Godhead dwells bodily.” Hebrews 1:3: “He is the brightness of His glory, and the express image of His person.” To know Jesus is to know God. To love Jesus is to love God. To worship Jesus is to worship God. To bow before Jesus is to bow before God. He is the knowable and touchable God. To the youth, to the man and woman in strength, to old age, and the hand of death seeking the touch of a hand on the other side of the river, He is to us the manifestation of the personal God [John 14:7].

And the fullness of the revelation of God is found in Him. As Paul wrote in 2 Corinthians 4:6: “For God, who commanded the light to shine out of darkness, hath shined in our hearts, to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ.” When God would give the light of the knowledge of His glory to men, how did He proceed? And to what did He direct our gaze? To the universe around us? No, though that proclaims the glory of the Lord [Psalm 19:1]. To the providences of life where He presides over history? No, though He weighs the nations like the fine dust in a balance [Isaiah 40:15]. To the astronomical stars that shine above us? No, He guides us to the face of Jesus Christ [2 Corinthians 4:6]. For the tears of Jesus are the pity of God, the gentleness of Jesus is the longsuffering of God, and the tenderness of Jesus is the love of God.

It was Thomas who looking upon our risen and glorified Lord said, “My God . . . My Lord” [John 20:26-28]. And it was John, seeing Him in His glory, falling at His feet as one dead, was touched by the right hand that in the days of His flesh was so often placed upon the shoulder of John: “Fear not; I am the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End: I am He that liveth, and was dead; and, behold, I am alive for evermore. . . and I have the keys of Hell and of Death” [Revelation 1:17-18]. Our Lord and our God: not strange or far-out, but reasonable, intelligently so. It is right. It is correct. It fits truth in heaven and earth to be a Christian: God and the reasoning mind. Now may we stand together?

Our Lord, there is no disciple who bowed at Thy feet by whose side we also would not bow. There is no heart that has ever called Thee Lord, by whose heart we also would not own Thee and confess Thee. There is no family that ever gathered around Thy blessed name and prayed, by whose side and in whose midst we wouldn’t feel at home. It seems so right to love Jesus, to pray in His name, to ask His comforting presence in the hour of need, to confess Thee unashamedly before men [Matthew 10:32], or to ask God’s blessings in strength as we follow after His nail-pierced feet. Lord Jesus, today may this be a day of salvation, may God add to His people. May God save our souls [Romans 10:8-13], forgive our sins [1 John 1:9], give us strength for the pilgrim way. In this moment when we quietly wait before God, a family you, a couple you, or just one somebody you, “Pastor, today I have decided for God, and here I come.” The family, bring them; your friend, or wife, or just you. And thank Thee, Lord, for the sweet harvest You give us, in Thy saving name, amen.

Down one of those stairways, down one of these aisles, our ministers are here; our deacons are here, the angels, God says, are here to welcome you. On the first note of this first stanza, take that first step, the greatest commitment you will ever make in your life. And God be with you as you come, while we wait, while we sing, and while we pray.

GOD AND

THE REASONING MIND

Dr. W.

A. Criswell

Acts 17:2

1-18-81

I. Introduction

A. Paul often

“reasoned”(Acts 17:2, 18:1, 4, 19, 24:24-25)

B. Our own minds seek

an answer

1. Plato –

characteristic of man that we seek answers

C. Others seek an

answer from us(1 Peter 3:15, Jude 3)

D. Freedom of spirit,

mind, and choice a gift from God

1. God addresses

His gospel to the mind, heart and soul(John 1:1)

2. It is an

intelligent and reasonable gospel

E. Paul’s appearance in

Athens

1.

Pagan polytheists had no problem adding another god(Acts

17:29-30)

2. Pagan philosophers

materialist atheists(Acts 17:18)

3.

Reasoning of Paul in another world – a personal, living God

II. The witness of the human heart (Acts 17:23, 27-28)

A. All

the philosophies of the world cannot stifle the instinctive hunger and cry of

the human heart for God

1.

Augustine’s Confessions

2.

Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy

B. Is

it possible we have this longing for God only to be mocked?

1.

Everything we see in the universe has design and purpose(Acts 17:28)

III. The witness of the reality of Christ(Acts 17:31, John 14:9)

A. The

world cannot bury Him

B.

He stands midmost in human history

C. The

express image of the invisible God(Colossians

1:15, 2:9, Hebrews 1:3)

D. He

is the full revelation of God(2 Corinthians 4:6,

John 20:28, Revelation 1:17-18)